| Plant Cell Rep |

| 10.1007/s00299-003-0610-0 |

Genetic Transformation and Hybridization

A. Lössl1 ![]() , C. Eibl1, 3,

H.-J. Harloff2, C. Jung2 and

H.-U. Koop1

, C. Eibl1, 3,

H.-J. Harloff2, C. Jung2 and

H.-U. Koop1

| (1) | Department of Botany, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, Menzinger Strasse 67, 80638 Munich, Germany |

| (2) | Institut für Pflanzenbau und Pflanzenzüchtung, Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel, Olshausenstrasse 40, 24098 Kiel, Germany |

| (3) | Present address: Icon Genetics, 85354 Freising, Germany |

| Andreas G. Lössl Email: loessl@botanik.biologie.uni-muenchen.de Fax: +49-89-1782274 |

Received: 16 August 2002 Revised: 31 January 2003 Accepted: 14 February 2003

Keywords Nicotiana tabacum - Phb operon - Plastid transformation - Polyhydroxybutyric acid

|

3HB |

3-Hydroxybutyric acid |

|

d.w. |

Dry weight |

|

CoA |

Coenzyme A |

|

GC |

Gas chromatography |

|

GPC |

Gel permeation chromatography |

|

HPLC |

High performance liquid chromatography |

|

Mn |

Molecular number average |

|

Mw |

Molecular weight average |

|

nt |

Nucleotide |

|

PHA |

Polyhydroxyalkanoate |

|

PHB |

Polyhydroxybutyrate |

|

UTR |

Untranslated region |

Polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) belongs to a class of polyesters of

3-hydroxy acids that are synthesized in various bacterial genera (Schubert et

al. 1988;

Hai et al. 2001).

These polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) are used as an energy source and also for

carbon storage.

In the bacterium Ralstonia eutropha, PHB is derived from

acetyl-coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA) by a sequence of three enzymatic reactions

(Schubert et al. 1988;

Slater et al. 1988).

First condensation of two molecules of acetyl-CoA is catalysed by

beta-keto-thiolase (EC 2.3.1.9) to form acetoacetyl-CoA. Acetyl-CoA reductase

(EC 1.1.1.36) then reduces acetoacetyl-CoA to ß-hydroxybutyryl-CoA, which is

then polymerized by PHB synthase (EC 2.3.1.-) to PHB. In R. eutropha the

genes for these enzymes are organized in a single operon (Peoples and Sinskey

1989).

There is considerable interest in PHAs, since they can be used as

biodegradable plastics and elastomers, which under optimal conditions are

degraded completely to CO2 and H2O. Additionally,

depending on the structure of the hydroxyacid side chains, the physical

properties of PHAs are extremely variable (Anderson and Dawes 1990;

Seebach and Fritz 1999).

Up to now, increased usage of PHAs has been restricted due to high

production costs. PHAs produced in bacterial fermenters are at least five times

more expensive than chemically synthesized polyethylene. Because of this, the

usability of bacterially generated PHAs is reduced to small-scale and special

applications. PHA production could be made more efficient by connecting its

bacterial biosynthetic pathway to chloroplast fatty acid metabolism (Poirier et

al. 1992).

Remarkable results were achieved in this area by nuclear

transformation of Arabidopsis (Nawrath et al. 1994;

Poirier 1999;

Bohmert et al. 2000)

and rapeseed (Houmiel et al. 1999).

However, nuclear transformation bears the potential risk of an undesired spread

of transgenic pollen into the environment. As pollen rarely transfers plastids

(Corriveau and Coleman 1988)

we decided to integrate the phb operon into the plastome.

In continuation of preliminary experiments reported by Lössl et al.

(2000),

we initially transferred the original R. eutropha phb operon, including

bacterial regulatory elements, to the tobacco plastome. In order to improve

genetic compatibility, we then replaced these elements of the phb operon

by a 5![]() region of plastid origin (Eibl et al. 1999),

which is expected to confer high expression.

region of plastid origin (Eibl et al. 1999),

which is expected to confer high expression.

Production of true 3HB polymer in plants has only been reported

previously using nuclear transformation (Poirier et al. 1992;

Nawrath et al. 1994;

Houmiel et al. 1999;

Bohmert et al. 2000).

In a recent preliminary communication, Nakashita et al. (2001)

claim PHB synthesis following plastid transformation; expression levels were,

however, extremely low, at only 8 ppm and no evidence for polymer

production was provided. We conclude that our present results provide the first

evidence for plastid transformation-mediated 3HB polymer production.

For integration of the phb operon with plastid expression

control elements, the transformation vector pKCZ was used (Zou 2001;

Huang et al. 2002).

This pUC19 based vector contains plastome homologous flanks including loci

trnN and trnR within the inverted repeat (IR) region. Plastome

insertion flanks for series P were located in IR-A (nt 109230–110348 and nt

110349–111520) and in IR-B (nt 131106–132277 and nt 132278–133396) respectively.

After PCR amplification by pfu polymerase the psbA promoter and

5![]() UTR

were linked to the 5

UTR

were linked to the 5![]() end of phbC in the pUC vector by ligation of

an NcoI-KpnI-cut fragment. This 5

end of phbC in the pUC vector by ligation of

an NcoI-KpnI-cut fragment. This 5![]() region was

transferred to pHBR68 (Schubert et al. 1988),

the phb operon-containing vector by cut and ligation of a

BamHI-AgeI fragment. In a final step the operon with 5

region was

transferred to pHBR68 (Schubert et al. 1988),

the phb operon-containing vector by cut and ligation of a

BamHI-AgeI fragment. In a final step the operon with 5![]() psbA motifs

was excised by SmaI and XhoI and transferred to transformation

vector pKCZ cut by SacII and XhoI, after generating blunt ends

using Klenow fragment.

psbA motifs

was excised by SmaI and XhoI and transferred to transformation

vector pKCZ cut by SacII and XhoI, after generating blunt ends

using Klenow fragment.

The construct contained the aadA resistance marker cassette

under control of the 16S-rDNA promoter downstream of the operon and was

terminated with the 3![]() -end (450 bp) of the Chlamydomonas reinhardtii

rbcL gene (Koop et al. 1996).

-end (450 bp) of the Chlamydomonas reinhardtii

rbcL gene (Koop et al. 1996).

Nicotiana tabacum L. cv. Petit Havana plantlets

(Surrow Seeds, Sakskøbing, Denmark) were grown from seeds in vitro at 25°C

(0.5–1 W/m2 Osram L85 W/25 universal-white fluorescent

lamps).

For particle gun mediated transformation (Svab et al. 1990),

DNA on the surface of gold particles (0.6 µm) was introduced into leaf

chloroplasts using a PDS1000He biolistic gun (DuPont). Selection and

regeneration of transgenic calli were carried out on RMOP medium (Svab et al.

1990).

After 4–6 cycles of repetitive shoot regeneration on spectinomycin and

streptomycin (500 mg/leach), shoots were transferred to B5

medium (Gamborg et al. 1968)

with spectinomycin for root formation.

DNA was extracted from 100–150 mg in vitro or greenhouse plant

material using the DNeasy plant DNA isolation kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). PCR

was carried out with the sense primer located in the transgene and the antisense

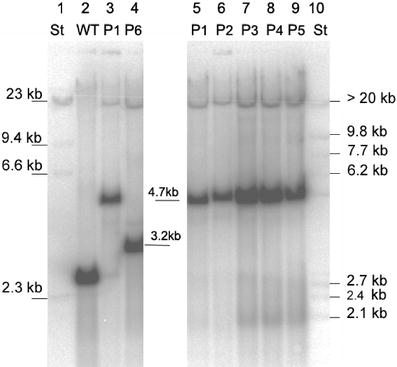

primer positioned in the plastome outside the vector flanks. For Southern blots,

3 µg digested total plant DNA was separated on 0.8% agarose gels. Blots

were prepared by transfer to nylon membranes (Hybond-N, Amersham). Specific

probes were random prime labelled with ![]() 32P using

Klenow fragment and hybridized to the membranes. Hybridization was carried out

overnight at 65°C in Church buffer (0.5 M sodium phosphate, pH 7.5 and

7% SDS). Filters were also hybridized simultaneously with a probe derived

from lambda DNA in order to detect size marker bands. Blots were washed twice at

50°C in 0.1% SDS and 2×SSC, pH7 for 30 min and once at 65°C in

0.1% SDS and 2×SSC for 30 min. Filters were exposed on imaging plates

for 8 h and signals were detected using a phosphoimager (BAS-1500, Fuji,

Tokyo).

32P using

Klenow fragment and hybridized to the membranes. Hybridization was carried out

overnight at 65°C in Church buffer (0.5 M sodium phosphate, pH 7.5 and

7% SDS). Filters were also hybridized simultaneously with a probe derived

from lambda DNA in order to detect size marker bands. Blots were washed twice at

50°C in 0.1% SDS and 2×SSC, pH7 for 30 min and once at 65°C in

0.1% SDS and 2×SSC for 30 min. Filters were exposed on imaging plates

for 8 h and signals were detected using a phosphoimager (BAS-1500, Fuji,

Tokyo).

Total RNA was isolated from 30–100 mg plant material (leaves)

using a RNeasy plant mini kit (Qiagen). About 5 µg RNA were separated on

1.2% formaldehyde-agarose gels and transferred to nylon membranes. Blotting was

carried out as described by Sambrook et al. (1989).

Random primed ![]() 32P-labelled DNA probes were hybridized to the membranes as

described for Southern blotting. Membranes were washed with 0.1×SSC,

0.1% SDS at 65°C. Signal strength was determined using the phosphoimager.

32P-labelled DNA probes were hybridized to the membranes as

described for Southern blotting. Membranes were washed with 0.1×SSC,

0.1% SDS at 65°C. Signal strength was determined using the phosphoimager.

PHB contents were measured in leaf material and callus. For monomer

determination, preextraction with ice-cold methanol was performed. PHB contents

were measured by gas chromatography using a 10m-CP-WAX-52CB column with a

diameter of 100 µm and 0.2 µm liquid phase. The procedure was adapted

to small volumes and a short GC column according to Brandl et al. (1988).

PHB contents were corroborated by HPLC after hydrolysis to crotonic

acid in 200 µl concentrated sulfuric acid for 60 min at 100°C. After

addition of 400 µl deionized water, 800 µl 15% ammonia and

200 µl 100 mM ammonium acetate (pH 4.6) followed by

0.22µ-filtration, 10–20 µl aliquots were injected into a Synergi Polar-RP

column, 150×2 mm, with 4 mm precolumn using 15 mM phosphoric acid

as eluent.

For molecular weight determination, 20 mg dry sample was

extracted in a fexIKA hot solvent extractor; 2 ml screw cap vials were

combined using a Kimble-Kontes 8-425 connector and two Teflon filters

(5–10 µm and 10–20 µm). Extraction was performed with 600 µl

dichloromethane in 40 cycles (87°C 1 min, 67°C 1 min, stirring at

600 ppm). Extract (10–20 µl) was applied to two GPC columns and a

precolumn in series provided by MZ Analysentechnik, Mainz: MZ-Gel Sdplus (5µ)

40×3 mm (106 Å) - 250×3 mm (106 Å) -

250×3 mm (105 Å). Columns were eluted with chloroform at

150 µl/min and 35°C. The eluent was monitored by an ERC-7512 RI detector.

The data collected by the Kontron HPLC system were converted into ASCII files

and Mw and Mn values were calculated with Microsoft Excel using chromatograms of

a polystyrene molecular weight standard mixture. The identity of the PHB peaks

in the GPC was checked by fractionation and subsequent GC measurement. If not

indicated otherwise, contents are given as proportions of dry weight.

In order to produce PHB in plastids we transferred the phb

operon from R. eutropha to the plastid genome of tobacco. For integration

of the operon, a plastome locus within the inverted repeat regions was targeted.

The map of the plastome insertion is shown in Fig. 1.

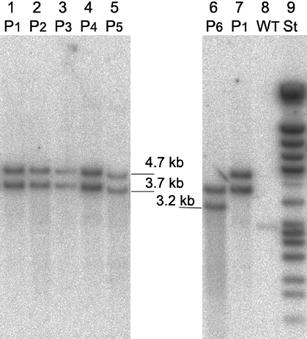

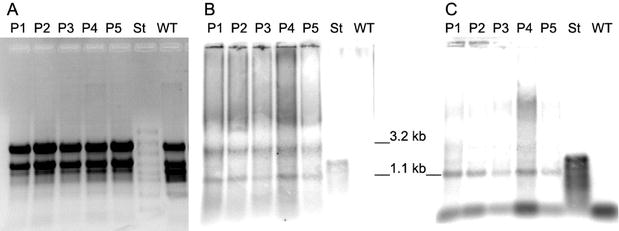

In the experiments presented, the operon containing the promoter and 5![]() -UTR of

the plastid psbA gene was inserted between the plastid genes trnN

and trnR. Five independent transformants P1-P5 were regenerated and

analysed for their PHB contents.

-UTR of

the plastid psbA gene was inserted between the plastid genes trnN

and trnR. Five independent transformants P1-P5 were regenerated and

analysed for their PHB contents.

Five confirmed transformant lines were analysed by GC, GPC and HPLC for their PHB contents.

For example, young leaf tissue of line P1 accumulated up to 17,442 ppm in dry weight in single PHB determinations. This corresponds to 1.7% PHB. On further growth the average PHB content of transformant lines declined to 20 ppm.

For the most highly expressing plants, the main part of 3HB was proven to be polymer by dichloromethane extraction prior to gas chromatography. In line P1 with high PHB expression, the proportion of extractable high molecular weight PHB was at least 75% of the total PHB determined in dry weight. Pre-extraction with cold methanol precipitation gave an estimate of monomer content of less than 14%.

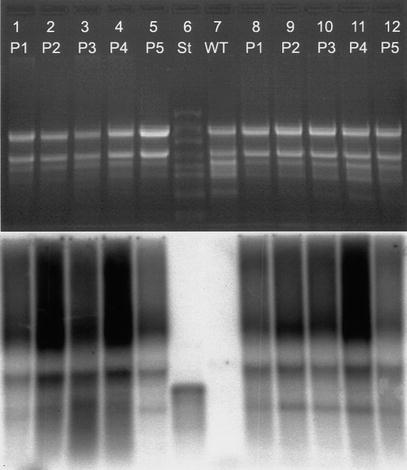

From the hybridization patterns detected we postulate the transcript arrangement given in Fig. 8. Variations in the RNA expression level between the genotypes of transformants were insignificant. There was no correlation to the variability found in their PHB synthesis. The genotype P1 with high PHB expression rates did not contain higher transcription levels than the transformants with low expression levels.

In order to test if the early developmental stage of the plants has an influence on PHB expression, in a further experiment, we compared the early regeneration stage with the following growth stage, in which the PHB content was decreasing. The plants P1 to P5 compared in this Northern analysis differed in their age. In the first set RNA was extracted from these plants directly after regeneration from callus and in the second set RNA was isolated from 3-week-old in vitro plants.

Expression of the genes for bacterial PHB synthesis in plastids has

the advantage of decreasing the risk of unwanted gene escape to the environment

via pollen. In addition, site-specific integration of transgenes in the plastome

generally allows a more predictable transformation event compared to nuclear

transformation (Poirier et al. 1992;

Nawrath et al. 1994;

Houmiel et al. 1999;

Saruul et al. 2002;

Menzel et al. 2002).

Here we report on significant PHB synthesis mediated by plastome-localized

transgenes. Hydroxybutyric acid was produced in tobacco following transformation

with an expression construct under plastid regulatory elements. PHB synthesis in

transplastomic plants carrying these constructs was determined in five plants

and selected material showed a PHB content of up to 1.7% in d.w. At least two

thirds of the PHB was shown to be polymer with a molecular weight in a range

between 100 and 1,000 kDa. These PHB contents exceeded the values measured

in previously reported transformants by more than three orders of magnitude

(Nakashita et al. 2001).

The data given in this report are in the same range as those derived from our

wild type control. PHB content of transgenic lines was highly variable. In

addition, we found that subclones, which were initially characterized as highly

accumulating, could show severely decreased PHB contents. Surprisingly there was

a strong dependence of the variation of PHB synthesis on the developmental stage

and growth conditions. More PHB was observed in heterotrophically grown tissue

culture material than in plants transferred to the greenhouse. Transcript

abundance did not correlate with the variability in PHB synthesis. In addition

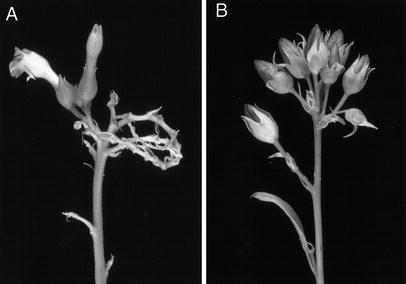

all positive lines showed growth retardation and male sterility.

It has been reported that up to 40% recombinant protein can

accumulate in transplastomic chloroplasts (De Cosa et. al. 2001)

if the gene- or reaction-products have no toxic effects on the cells. The

expression of plastome-located transgenes mainly depends on the regulatory

elements used and on turnover of the respective proteins or on the insertion

sites used (Eibl et al. 1999;

Staub et al. 2001;

Ye et al. 2001).

Expression may also be influenced negatively if the material is heteroplastomic,

as segregation events may cause a reduction of the copy number of the

recombinant plastome. However Southern analysis of tissue culture material grown

under spectinomycin selection showed that no wild type plastome was detectable.

An additional Southern hybridization analysis revealed that the plants were

homoplastomic following a 3-month period in the greenhouse. Therefore

heteroplastomy cannot be the reason for reduced PHB contents.

There are at least two reasons besides heteroplasmy which could

possibly cause PHB expression as low as only 8 ppm as presented by

Nakashita et al. (2001).

It is theoretically possible that the low expression was due to a non-neutral

insertion locus and that positioning between rbcL and accD gene

was silencing the PHB expression. On the other hand it is possible that

mutations occurred within the operon.

Another important difference compared to Nakashita et al. (1999)

is expression through plastid regulatory elements. Instead of an approach with

the unchanged bacterial expression cassette, a different 5![]() regulatory element

was used for establishment of the PHB pathway in the chloroplast. In our

transformants the plastid promoter and 5

regulatory element

was used for establishment of the PHB pathway in the chloroplast. In our

transformants the plastid promoter and 5![]() -UTR from the

psbA gene were fused to the phb operon. It is known that both the

psbA promoter and the psbA 5

-UTR from the

psbA gene were fused to the phb operon. It is known that both the

psbA promoter and the psbA 5![]() -UTR confer very

strong gene expression (Kulkarni and Golden 1994).

Expression is enhanced in the light and shows some tissue specificity, which

leads to increased expression in chloroplasts of photosynthetically active

tissues (Stern 1997;

Bruick and Mayfield 1999).

Due to the plastid derivation of the psbA motifs it is assumed that the

transcription rates of the three genes in this expression cassette are much

higher than with bacterial motifs. In addition, the translation efficiency of

the synthase gene (phbC) under control of the psbA 5

-UTR confer very

strong gene expression (Kulkarni and Golden 1994).

Expression is enhanced in the light and shows some tissue specificity, which

leads to increased expression in chloroplasts of photosynthetically active

tissues (Stern 1997;

Bruick and Mayfield 1999).

Due to the plastid derivation of the psbA motifs it is assumed that the

transcription rates of the three genes in this expression cassette are much

higher than with bacterial motifs. In addition, the translation efficiency of

the synthase gene (phbC) under control of the psbA 5![]() -UTR should be

superior compared to the phbC translation driven through the bacterial

regulatory elements. Translation of the phbA and phbB genes could

be improved further by using adequate plastid spacer elements. This is relevant,

as our results suggest that limitation of PHB synthesis at least did not depend

on transcript abundancy. Transcript analysis has shown that there is no

significant difference in the transcript expression rates between the PHB

synthesizing genotypes. Experiments comparing the growth stages in which the

highest PHB variability was observed have shown that these developmental stages

do not affect transcript expression of the phb genes. These findings

strongly indicate that the high variability of PHB content is not due to RNA

expression but rather to posttranscriptional regulation events.

-UTR should be

superior compared to the phbC translation driven through the bacterial

regulatory elements. Translation of the phbA and phbB genes could

be improved further by using adequate plastid spacer elements. This is relevant,

as our results suggest that limitation of PHB synthesis at least did not depend

on transcript abundancy. Transcript analysis has shown that there is no

significant difference in the transcript expression rates between the PHB

synthesizing genotypes. Experiments comparing the growth stages in which the

highest PHB variability was observed have shown that these developmental stages

do not affect transcript expression of the phb genes. These findings

strongly indicate that the high variability of PHB content is not due to RNA

expression but rather to posttranscriptional regulation events.

It is questionable if a nonspecific start of transcription or

processing event is leading to RNA transcripts that cannot be translated

correctly. A processing event can largely be excluded, as an endonucleolytic cut

would result in two transcripts of the same stoichiometric amounts. However,

this was not the case; we could find the 3.2 kb and 1.1 kb transcripts

in variable ratios. Additionally, PHB was formed in these plants and therefore

we believe that there were intact transcripts containing the complete set of

phb genes.

In R. eutropha, it has been suggested that the phbC

promoter drives transcription up to the termination signal at the end of the

operon (Schubert et al. 1988).

However, Oelmüller et al. (1990)

described phb transcripts smaller than 4.2 kb in A.

eutrophus. Peoples and Sinskey (1989)

did not rule out a second promoter within the phb operon. Sequence

alignment did not reveal any putative transcription initiation site. Further

steps are intended, to investigate if the transcripts are intact and edited

correctly.

Regulation of protein levels could be another reason for

posttranscriptional downtuning of PHB synthesis. Apart from the untranslated

5![]() regions of the transcripts, which control translation efficiency (Eibl et

al.1999),

proteases, in particular, have a high impact on every step of plant development

(Huffaker 1990;

Estelle 2001).

Low production can be due to degradation of one or all of the PHB forming

enzymes by plastid proteases directly after translation. Another possibility for

variability in PHB production is the suggestion that proteolytic activity

interacts with metabolic factors, depending on energy supply.

regions of the transcripts, which control translation efficiency (Eibl et

al.1999),

proteases, in particular, have a high impact on every step of plant development

(Huffaker 1990;

Estelle 2001).

Low production can be due to degradation of one or all of the PHB forming

enzymes by plastid proteases directly after translation. Another possibility for

variability in PHB production is the suggestion that proteolytic activity

interacts with metabolic factors, depending on energy supply.

The dependence of PHB accumulation on growth conditions is an

important issue. There seems to be a clear reduction in PHB synthesis under

photoautotrophic conditions. The highest PHB concentrations were found in tissue

culture material cultivated on sugar-containing medium under moderate

illumination. Almost no PHB could be detected in leaves of greenhouse-grown

seedlings, although the presence of the transgenes in a continued homoplastomic

state was confirmed by Southern analysis. Growth was retarded in tissue that had

accumulated considerable PHB amounts, whereas in rapidly growing tissue PHB

synthesis was reduced.

The large amounts of PHB, up to 1.7%, that were found in leaves of

heterotrophically grown material may have been a consequence of slow PHB

accumulation during retarded growth under conditions where energy was available

in excess. We conclude that in tobacco a significant PHB accumulation can only

be achieved if a sufficient pool of the acetyl-CoA precursor is available.

Consequently, improvement of PHB synthesis in tobacco may only be reached by

adjusting the acetyl-CoA levels, since there is a corresponding negative

relationship between growth and PHB accumulation.

Growth reduction and sterility were also reported for nuclear

transformed Arabidopsis, although the PHB content was much higher in

these plants (Poirier et al. 1992;

Nawrath et al. 1994;

Bohmert et al.2000).

In addition to reduced PHB synthesis under greenhouse conditions,

the transformants were male sterile. It is well known that cytoplasmic

incompatibilities manifest themselves in pollen sterility (Kempken and Pring

1999).

Mature PHB plants showed a phenotype similar to wild type tobacco, but the

flowers were sterile. It is not known whether the PHB-synthesizing enzymes

themselves are responsible for sterility or if the male sterility is a

consequence of metabolic factors. Recent results from Bohmert et al. (2002),

who have expressed the phbA gene from an inducible promoter, demonstrate

that constitutive expression of the ß-ketothiolase gene has detrimental effects

on transformation efficiency. Interactions of ß-ketothiolase with other

proteins or metabolites or depletion of acetyl-CoA from the plastid metabolism

could be responsible for the flower sterility observed. In addition, as

suggested by Bohmert et al. (2002)

toxic effects through phbA gene expression could be due to the

intermediates of PHB biosynthesis, acetoacetyl-CoA and 3-hydroxybutyryl-CoA.

Our results have shown that PHB synthesis in plastids is feasible in

principle. However, significant PHB contents were restricted to plants of tissue

culture origin. In mature greenhouse grown plants the PHB content was extremely

low. This is apparently due to intolerance of the new pathway in tobacco.

Tobacco still serves as a model plant for novel transgene expression systems;

however, even 1.7% PHB in dry weight would be too low for profitability and

industrial applications of transplastomic PHB plants are still far away. A

solution to the problem of inhibitory effects might be to use an inducible PHB

gene expression system.

References

| Anderson AJ, Dawes EA (1990) Occurrence, metabolism, metabolic role and industrial uses of bacterial polyhydroxy alkanoates. Microbiol Rev 54:450–472 |

| Bohmert K, Balbo I, Kopka J, Mittendorf V, Nawrath C, Poirier Y, Tischendorf G, Trethewey R, Willmitzer L (2000) Transgenic Arabidopsis plants can accumulate polyhydroxybutyrate to up to 4% of their fresh weight. Planta 211:841–845 |

| Bohmert K, Balbo I, Steinbuchel A, Tischendorf G, Willmitzer L (2002) Constitutive expression of the beta-ketothiolase gene in transgenic plants. A major obstacle for obtaining polyhydroxybutyrate-producing plants. Plant Physiol 128:1282–1290 |

| Brandl H, Gross RA, Lenz RW, Fuller RC (1988) Pseudomonas oleovorans as a source of poly(ß-) hydroxyalkanoates for potential applications as biodegradable polyesters. Appl Environ Microbiol 54:1977–1982 |

| Bruick R, Mayfield S (1999) Light-activated translation of chloroplast mRNAs. Trends Plant Sci 4:190–195 |

| Corriveau JL, Coleman A (1988) Rapid screening method to detect potential biparental in-heritance of plastid DNA: results for over 200 angiosperm species. Am J Bot 75:1443–1458 |

| De Cosa B, Moar W, Lee SB, Miller M, Daniell H (2001) Overexpression of the Bt cry2Aa2 operon in chloroplasts leads to formation of insecticidal crystals. Nat Biotechnol 19:71–74 |

| Eibl C, Zhurong Z, Beck A, Minkyun K, Mullet J, Koop HU (1999) In vivo analysis of plastid psbA, rbcL and rpl32 UTR elements by chloroplast transformation: tobacco plastid gene expression is controlled by modulation of transcript levels and translation efficiency. Plant J 19:333–345 |

| Estelle M (2001) Proteases and cellular regulation in plants. Curr Opin Plant Biol 4:254–260 |

| Gamborg OL, Miller RA, Ojima K (1968) Nutrient requirements of suspension cultures of soybean root cells. Exp Cell Res 50:151–158 |

| Hai T, Hein S, Steinbüchel A (2001) Multiple evidence for widespread and general occurrence of type-III PHA synthases in cyanobacteria and molecular characterization of the PHA synthases from two thermophilic cyanobacteria: Chlorogloeopsis fritschii PCC 6912 and Synechocystis strain MA19. Microbiology 147:3047–3060 |

| Houmiel KL, Slater S, Broyles D, Casagrande L, Colburn S, Gonzalez K, Mitsky TA, Reiser SE, Shah D, Taylor NB, Tran M, Valentin HE, Gruys KJ (1999) Poly(beta-hydroxybutyrate) production in oilseed leucoplasts of Brassica napus. Planta 209:547–550 |

| Huang FC, Klaus SM, Herz S, Zou Z, Koop HU, Golds TJ (2002) Efficient plastid transformation in tobacco using the aphA-6 gene and kanamycin selection. Mol Genet Genomics 268:19–27 |

| Huffaker R (1990) Proteolytic activity during senescence of plants. New Phytol 116:199–231 |

| Kempken F, Pring DR (1999) Male sterility in higher plants: fundamentals and applications. Prog Bot 60:139–166 |

| Koop HU, Steinmüller K, Wagner H, Roessler C, Eibl C, Sacher L (1996) Integration of foreign sequences into the tobacco plastome via polyethylene glycol-mediated protoplast transformation. Planta 199:193–201 |

| Kulkarni RD, Golden S (1994) Adaptation to high light intensity in Synechococcus sp. strain PCC 7942: regulation of three psbA genes and two forms of the D1 protein. J Bacteriol 176: 959–965 |

| Lössl A, Eibl C, Dovzhenko A, Winterholler P, Koop HU (2000) Production of polyhydroxybutyric acid (PHB) using chloroplast transformation. The 8th international symposium on biological polyesters (ISBP 2000), 11 September 2000–15 September 2000, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Mass., USA |

| Menzel G, Harloff HJ, Jung C (2002) Expression of bacterial poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) synthesis genes in hairy roots of sugar beet (Beta vulgaris L.) Appl Microbiol Biotechnol (in press) |

| Nakashita H, Arai Y, Yoshioka K, Fukui T, Doi Y, Usami R, Horikoshi K, Yamaguchi I (1999) Production of biodegradable polyester by a transgenic tobacco. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 63:870–874 |

| Nakashita H, Arai Y, Shikanai T, Doi Y, Yamaguchi I (2001) Introduction of bacterial metabolism into higher plants by polycistronic transgene expression. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 65:1688–1691 |

| Nawrath C, Poirier Y, Somerville C (1994) Targeting of the hydroxybutyrate biosynthetic pathway to the plastids of A. thaliana results in high levels of polymer accumulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91:12760–12764 |

| Oelmüller UN, Krüger N, Steinbüchel A and Friedrich C (1990) Isolation of prokaryotic RNA and detection of specific mRNA with biotinylated probes. J Microbiol Methods 11:73–81 |

| Peoples OP, Sinskey AJ (1989) Poly-beta-hydroxybutyrate PHB biosynthesis in Alcaligenes eutrophus H16. Identification and characterization of the PHB polymerase gene phbC. J Biol Chem 264:15298–15303 |

| Poirier Y (1999) Production of new polymeric compounds in plants. Curr Opin Biotechnol 10:181–185 |

| Poirier Y, Dennis DE, Klomparens K, Somerville C (1992) Polyhydroxybutyrate, a biodegradable thermoplastic in transgenic plants. Science 256:520–523 |

| Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T (1989) Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd edn. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y. |

| Saruul P, Srienc F, Somers DA, Samac DA (2002) Production of a biodegradable plastic polymer, poly-ß-hydroxybutyrate, in transgenic alfalfa. Crop Sci 42:919–927 |

| Schubert P, Steinbüchel A, Schlegel HG (1988) Cloning of the A. eutrophus genes for synthesis of poly-ß-hydroxybutyric acid (PHB) and synthesis of PHB in E. coli. J Bacteriol 170:5837–5847 |

| Seebach D, Fritz M (1999) Detection, synthesis, structure, function of oligo(3-hydroxyalkanoates): contributions by synthetic organic chemists. Int J Biol Macromol 25:217–236 |

| Shinozaki K, Ohme M, Tanaka M, Wakasugi T, Hayashida N, Matsubayashi T, Zaita N, Chunwongse J, Obokata J, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Ohto C, Torazawa K, Meng BY, Sugita M, Deno H, Kamogashira T, Yamada K, Kusuda J, Takaiwa F, Kato A, Tohdoh N, Shimada H, Sugiura M (1986) The complete nucleotide sequence of the tobacco chloroplast genome: its gene organization and expression. EMBO J 5:2043–2049 |

| Slater SC, Voige WH, Dennis DE (1988) Cloning and expression in E. coli of the A. eutrophus H16 poly-ß-hydroxybutyrate biosynthetic pathway. J Bacteriol 170:4431–4436 |

| Staub JM, Garcia B, Graves J, Hajdukiewicz PTJ, Hunter P, Nehra N, Paradkar V, Schlittler M, Carroll JA, Spatola L, Ward D, Ye G, Russell DA (2000) High-yield production of a human therapeutic protein in tobacco chloroplasts. Nat Biotechnol 18:333–338 |

| Stern DB, Higgs DC, Yang J (1997) Transcription and translation in chloroplasts. Trends Plant Sci 2:308–315 |

| Svab Z, Hajdukiewicz P, Maliga P (1990) Stable transformation of plastids in higher plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 87:8526–8530 |

| Ye GN, Hajdukiewicz PT, Broyles D, Rodriguez D, Xu CW, Nehra N, Staub JM (2001) Plastid-expressed 5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase genes provide high level glyphosate tolerance in tobacco. Plant J 25:261–270 |

| Zou Z (2001) Analysis of cis-acting expression

determinants of the tobacco psbA 5 |

|

Back To Overview Back to Home Page Loessl: Cytoplasm Genome Research

|